Hey! Welcome to Marginal Futility. Here, I share interesting things I come across, especially related to business, finance and tech. You can find my previous posts here.

A happy update - Marginal Futility has now crossed 1000 subscribers; I would love it if you could share this blog with people who you think would find it interesting.

You can subscribe below if you wish to receive updates directly in your mailbox. No spam, ever! :) You can also follow me on Twitter here.

On to today’s post.

Let’s take a hypothetical situation.

I offer you an investment product “X” whose current value is Rs. 100.

But then, I add two very interesting features to X.

You won’t know what it trades at on a day-to-day basis. I (and only I) will be the one to tell you how much it is “worth” and I will do that very infrequently, let’s say, once a year

You can’t just sell it when you want to, you are locked in for a long period, let’s say, 10 years.

Now, you probably would be thinking - Wow, these features are not features, they are bugs. There is no chance I am paying Rs.100 now.

Essentially, you would demand a higher rate of return for holding this investment.

If you do so, you are not alone of course. Corporate finance theory does suggest that investors would pay less for an asset which is illiquid and has opaque pricing.

We will come back to this.

…

Late last year, Bloomberg came up with an interesting article on Tiger Global.

What caught my eye was the following section:

Tiger Global Management started out as a traditional stock-picking hedge fund that dabbled in venture investments. Now, after a tumultuous 2022, its startup bets outstrip equities more than ever before.

That transformation helped the money manager weather its worst year on record, as Tiger Global’s traditional hedge fund lost more than half of its value. Its long-established venture unit grew exponentially over the past two years, insulating the firm from even steeper losses, as such private investments are less susceptible to declines in public equities or the short-term whims of clients.

Private investments are less susceptible to declines as compared to public equities?

…

Let’s look at some data:

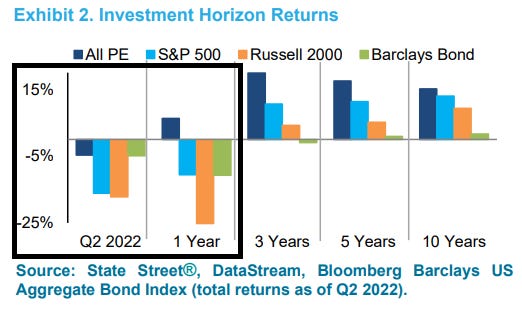

Here is the latest available data on PE performance from State Street Advisors (upto mid-2022).

The highlighted section is quite interesting - during a period when the S&P 500 as well as Russell 2000 fell by a lot; the PE index didn’t fall as much (and was actually positive for the year)

Another interesting chart by Cambridge Associates below:

From 1994-2017; there were 4 years when the public markets gave negative returns; but not a single year (not even 2008) when PE gave negative returns!

So what the Bloomberg article above said seems correct; private investments do indeed seem less susceptible to declines as compared to public equities

…

One probable reason for such performance can of course be that PE, as an asset class, is not correlated to the public markets.

However, as the below table from JPM Asset Management shows, this isn’t true.

Correlation between global equities and private equity has been 0.8 from 2008 to 2Q2022.

…

So then why this gap between public and private returns?

Unlike public stocks, private equity valuations aren’t marked to market every day. Their valuations are determined either by the next round of funding or secondary deals; or at the discretion of the fund manager.

A common argument is that this is the correct way; public markets can and often are quite irrational; and private equity managers can take a longer term view of companies and accordingly mark their investments

Here’s what Christopher Schelling says while arguing that PE gets its valuation right:

The frictionless ease of transaction in public markets means it’s extremely easy to over- or underreact. On the other hand, in private markets, it is precisely the friction of transaction that prevents frivolous pricing. Private markets force market participants to engage rational, System 2 thinking.

With capital locked up, there is no need for the fund to access immediate liquidity. The option to be a seller when it’s advantageous accrues to the owner. Hence, there is also no need to “mark to market.”

Interim valuations don’t really matter!

…

We could argue that private markets are more long term in nature; and less affected by whims and fancies and irrational exuberance or fears of public markets; but in the end, private companies are also subject to the same macroeconomic and sector-specific tailwinds as well as headwinds as public counterparts.

So can the gap in valuations be justified?

…

Remember the hypothetical situation from the beginning? Let’s take another situation

You come to me and say, “Hey, I need an investment product. But I want a really long term investment, and I don’t want to be bothered by the day to day fluctuations. I look at my stock investments fluctuating every day, and I hate the volatility. I am worried I will take some counterproductive buy/sell calls because of this.”

And I tell you - Yes, ofcourse. I have an investment product “X”. Now normally, I would have sold it to you for 100, but given your special requests, I will do two things for you, and only for you.

I will not tell you what it trades at on a day-to-day basis; you don’t need to bother about these short term fluctuations after all! I will ofcourse use my best judgement to tell you how much it is worth once a year

I will make sure you can’t sell it for a long time, let’s say 10 years. I understand and appreciate that you want to be a long term investor.

For the above features, I will charge you a bit extra over 100.

Essentially, you would get a slightly lower rate of return for holding this investment.

The above also, kind of, makes sense?!

…

From AQR’s blog “The Illiquidity discount”

Conventional wisdom is you get an expected return premium for bearing illiquidity. Illiquidity is a bad thing, and, all else equal, you need to be paid extra for taking it on. But, what if this is backwards? What if investors will actually pay a higher price and accept a lower expected return for very illiquid assets?

Volatility sucks. Are investors willing to pay a higher price (and in return, accept lower returns) to avoid volatility?

Maybe the illiquidity and pricing opacity of private equity is a large part of why LPs find it attractive.

…

Here’s what Matt Levine says about this:

Classically investors in private companies buy shares at relatively low valuations, and then the companies go public at higher valuations and the early investors get rich, and part of the explanation for the difference is liquidity: The early investors get limited liquidity before the initial public offering, the public investors get total liquidity after the IPO, and so the public investors will pay more for more of a good thing (liquidity).

But in recent years this has not always been true, and lots of big tech unicorns have gone public and been worth less than, or not much more than, their earlier private valuations.

One possible explanation for this is just an unlucky run of mistakes. (But).. Perhaps it is at least psychologically soothing for the private investors to not have to worry about stock-price volatility, and they are willing to pay up for the pleasant experience of not being told they’re losing money.

By being illiquid, the private equity fund can look less volatile. Getting similar returns with less volatility is good; getting similar returns and feeling like you have less volatility also might be good.

If investors want illiquidity then they have to pay for it, and the way you pay for anything in financial markets is by accepting lower expected returns. The reason that unicorn valuations were often higher than the public market would bear might have been that investors enjoyed the unicorn experience more than the public-market experience. They just didn’t enjoy how it ended.

…

Now look, this is how things have worked and probably will; and that’s fine.

But I think there are a few important implications which arise out of this.

Implication 1: For capital allocators

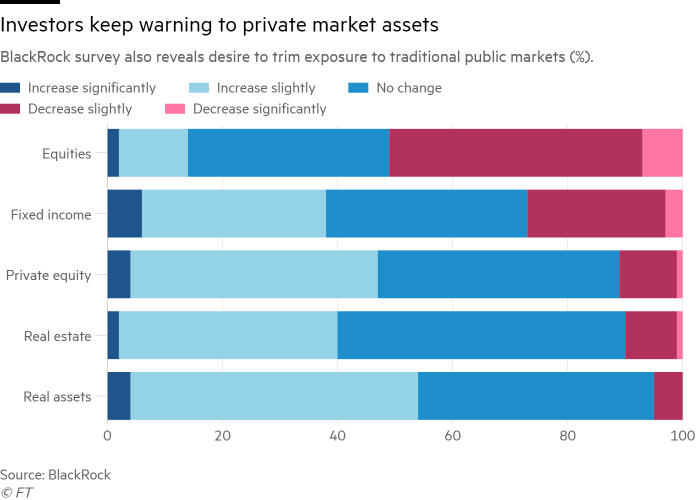

Increasing allocation to private equity basis an illusion of higher risk-adjusted returns; where risk is measured in terms of volatility

Lack of frequent MTM leads to artificial smoothening of returns; leading to significantly lower measures of volatility and beta; and a seemingly low correlation to public markets.

When interest rates were low, capital allocators were drawn to buy-outs and venture capital due to their high reported returns. However, now that the public markets are not doing that well, it seems PE’s lower volatility is the bigger selling point.

The goal of capital allocators like pension funds is to generate the highest risk-adjusted returns for the people they are serving.

Now if the lower volatility is actually just a factor of less-frequent marking to market; and if the underlying risk is actually not much lesser than public equities; does giving up some returns for merely the appearance of lower risk doing right by the constituents?

…

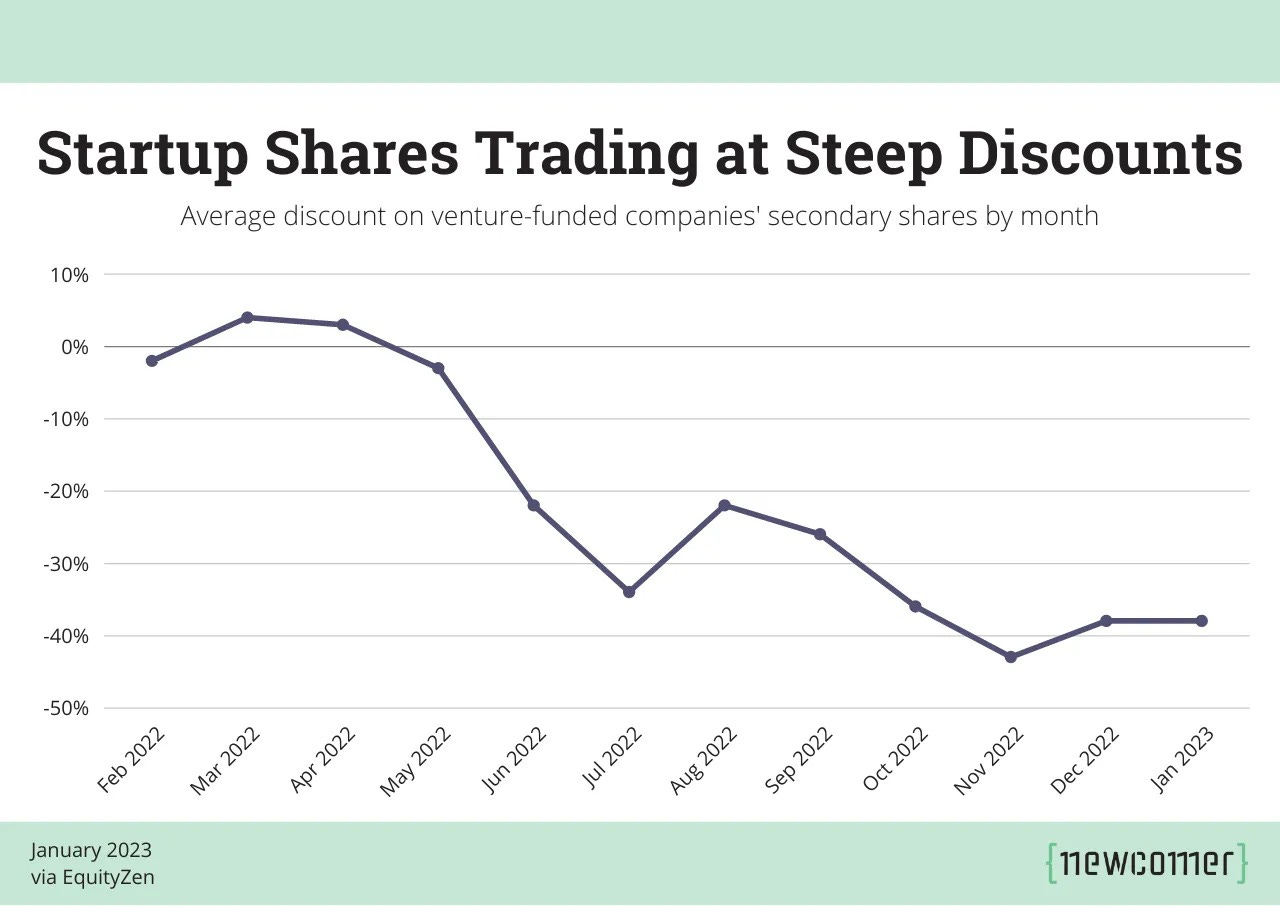

Implication 2: For companiesCompanies will face valuation pressure when they eventually decide to go public

As of end-2022, there are 806 private tech companies valued at more than USD 1bn (unicorns), while there are only 278 of such companies in the public market!

We have seen the valuation pressure play out in a lot of Indian and global startups going public over the last year.

A second order implication would be companies staying private longer.

The median age of US companies doing an IPO has been trending upwards. The below exhibit shows that the median age of a company doing an IPO was ~8 years from 1976 to 1997 which increased to ~11 years from 1998 to 2019

…

Implication 3: For employeesStock options are often valued basis the latest available valuation (which may not be appropriately marked to market); and a lot of them will be underwater

Many workers are heading into roles at several funded companies unaware that the company they’re joining might be overvalued (as compared to public markets and not been adequately marked-to-market) and that, as its valuation becomes more in line with public equity valuations, their ESOPs might be worth a lot less than they used to be.

…..

“Salience” is a well-known idea in behavioral finance and psychology. What it means is - if you are observing something you might overreact to it, but if you’re not reminded of it you might tend to ignore it.

But, how much ignorance is too much? :)

Interesting things I read this week

I solved the mystery of afternoon slump through CGM by Ankush Datar

I wore a CGM for four months and learnt what was right for my body. I made tangible changes in my everyday behaviour — changing the order in which I ate my food — after seeing real-time data. I understood how my dietary choices affected my energy levels and cognitive performance. And, of course, it helped me solve my afternoon slump problem

AI and the Big Five by Ben Thomson (Stratechery)

The story of 2022 was the emergence of AI, first with image generation models, including DALL-E, MidJourney, and the open source Stable Diffusion, and then ChatGPT, the first text-generation model to break through in a major way. It seems clear to me that this is a new epoch in technology. Given the success of existing companies with new epochs, the most obvious place to start when thinking about the impact of AI is with the big five: Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft.

In praise of friction by Tanay Jaipuria

At a high level, friction can sometimes lead to better outcomes for both the user and the company building a product in a few key ways: preventing users from making bad decisions, serving as a form of self-regulation and increasing positive actions from users via “commitment” or skin-in-the-game.

Thank you for reading! Please share it with people who you think might find it interesting :)

You can also follow me on Twitter here.

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)

Loved the piece... the question also is that why eventually private companies go public? Is it better price discovery owing to wider ownership or ability to raise more capital? or it is just exit to existing investors?

All the three can be taken care of by remaining private. In fact all the tree are better taken care off by remaining private

Also by going public the regulatory and investor pressure is only increasing and more often changes the focus of management / organization...

According to you what should be the key considerations for going public?