[#11] Commoditizing your complements

An interesting, and sometimes more effective, alternative to vertical integration

Hey! Welcome to Marginal Futility. This blog is my attempt to summarize and share some interesting things I come across, especially related to business, finance and tech. I have previously written about the power law in venture capital, business lessons from Amazon and common errors in estimating market size. You can find the full archive here.

You can subscribe below if you wish to receive updates directly in your mailbox. No spam, ever! :)

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)

On to today’s article…

Vertical integration is a commonly seen practice – moving up and/or down the value chain to capture more economic profit. However, vertical integration is quite complex, generally requires huge investments, is difficult for smaller companies to implement, and of course, beyond a certain point, has the risk of running afoul of anti-trust / monopoly regulations.

There is an alternative – “Commoditizing the complements”, wherein a company makes other layers of the value chain (in which it is not present) less valuable, thereby keeping a major part of the economic profit for itself (or the layer in which it is present).

Understanding complements:

A complement is a good that is dependent on, or requires use of another product. For example, cars and fuel are complementary products, and so are printers and ink.

Lets say Product A and B are complementary.

A set of consumers can allocate a value of X between the two goods.

A company can decide to sell both A and B and capture X (possibly through vertical integration). Or it can decide to dominate in the market of A, while commoditizing B, so that maximum value flows to product A. This is the idea behind ‘Commoditizing complements’.

So what does ‘commoditizing complements’ actually mean?

It means making complementary products as cheap and ubiquitous as possible.

All else being equal, demand for a product increases when the prices of its complements decrease. For reducing the price of complements, a company would need to ensure heavy competition amongst the suppliers / developers who are producing the complements.

From Strategy Letter V by Joel Spolsky (co-founder of Stack Overflow):

…In general, a company’s strategic interest is going to be to get the price of their complements as low as possible. The lowest theoretically sustainable price would be the “commodity price”—the price that arises when you have a bunch of competitors offering indistinguishable goods.

…

Understanding Value chains and the ‘distribution’ of value

Generally, value chain is the framework that we use to describe how an industry and particular businesses in it are organized. Here’s how Michael Porter defined it in his book ‘Competitive Advantage’:

Value chain analysis is the process of looking at the activities that go into changing the inputs for a product or service into an output that is valued by the customer.

In this model, an industry can be seen as a succession of many suppliers, producers, and distributors.

Traditionally, competitive strategy has focused on competitors, suppliers, and customers. Think about the five forces framework conceptualized by Porter in 1979: New entrants, suppliers, buyers, substitutes and competitive rivalry.

This model was extended in the mid 1990s to account for one more ‘force’ - Complementary goods.

From the book ‘Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the network Economy’ published in 1999,

… In the information economy, companies selling complementary components, or complementors, are equally important. When you are selling one component of a system, you can’t compete if you’re not compatible with the rest of the system…The dependence of information technology on systems means that firms must focus not only on their competitors but also on their collaborators. Forming alliances, cultivating partners, and ensuring compatibility (or lack of compatibility!) are critical business decisions…

The commonly accepted logic is that competition generally happens amongst substitutes. But taking the lens of a value chain and total consumer surplus, you will see that there is actually intense competition between complements - Not every level in the value chain makes the same returns.

Side Note: Typically, value chains are thought of as a linear flow: outputs in one part become inputs of the next part. However, several products (especially in tech) are structured as stacks and not flows: several components come together, at the same time, to become the final product / service / experience.

One of the best examples to understand the concept of commoditizing complements is seeing what IBM and Microsoft did early on.

This is how Joel Spolsky explains it:

When IBM deigned the PC architecture, they used off-the-shelf parts instead of custom parts, and they carefully documented the interfaces between the parts. Why? So that other manufacturers could join the party. As long as you match the interface, you can be used in PCs. IBM’s goal was to commoditize the add-in market, which is a complement of the PC market, and they did this quite successfully. Within a short time (several) companies sprung up offering memory cards, hard drives, graphics cards, printers, etc. Cheap add-ins meant more demand for PCs.

When IBM licensed the operating system PC-DOS from Microsoft, Microsoft was very careful not to sell an exclusive license. This made it possible for Microsoft to license the same thing to Compaq the other hundreds of OEMs who had legally cloned the IBM PC using IBM’s own documentation. Microsoft’s goal was to commoditize the PC market. Very soon the PC itself was basically a commodity, with ever decreasing prices, consistently increasing power, and fierce margins that make it extremely hard to make a profit. The low prices, of course, increase demand. Increased demand for PCs meant increased demand for their complement, MS-DOS.

…

Some more examples:

Example 1: Google (Android OS)

Google distributes the open source licensed version of Android at no cost to handset makers. Despite being the leading mobile OS in the world, Google does not earn anything directly from Android OS. However, it earns money when people use Google services embedded in Android OS. In most markets, Google locks its OS with its Play Store, its APIs and its advertising services. That effectively means every Android user consumes Google services, no matter which handset maker’s phone he/she is using. Imagine a scenario where Android was not free / not available to other handset makers (like iOS). Would we see a plethora of smartphone manufacturers? I assume No. The money and time cost of building own OS as well as building an app marketplace with enough network effects would be prohibitive for most smartphone manufacturers.

Android's goal is to increase competition amongst smart phones manufacturers by reducing their cost of development and manufacturing (by removing the cost of software and building an app store) since smart phones are complements of Google's web-based services. By commoditizing (to an extent) the smartphone layer in the value chain by making Android free, Google has effectively driven the demand for its core advertising business.

Example 2: Apple (App Store)

Continuing from the previous example, if we draw out a rough value chain for smartphones, we have the manufacturers (hardware), the mobile OS developers (software) and the user applications developers. Of course, there would be a further breakdown in these components: for example, hardware manufacturers would include chip manufacturers, handset manufacturers, battery manufacturers and so on..

By launching App Store, Apple effectively commoditized the third layer above - of user applications. By making it easy for anyone to build and distribute an app, Apple managed to foster an immense price competition among developers, while taking a cut (~30%) out of each paid download.

Applications are one of the core reasons why users flocked to buy Apple devices. Remember the slogan for the early iPhone ads? - “There’s an app for that”. By reducing the price (and value) of apps, Apple managed to drive demand for its core product- devices.

Example 3: Tesla (?)

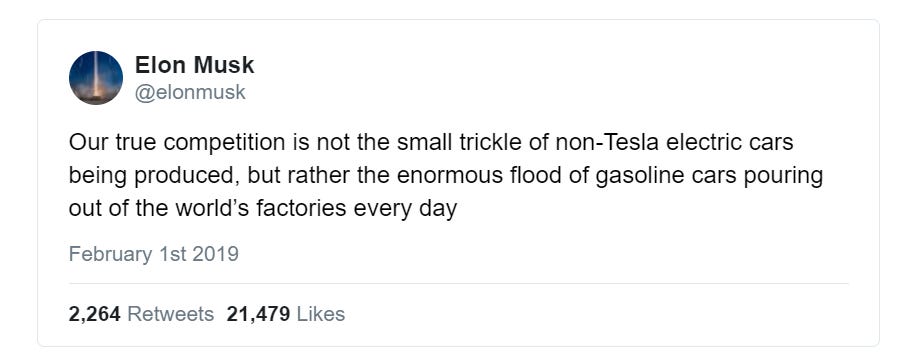

In 2014, Tesla made all its patents public - anyone could use them for free. Elon Musk said that this would allow the electric vehicle market to grow more rapidly.

In 2014, Tesla was producing only around 40,000 vehicles annually. Even after significant investments, Tesla’s most recent quarterly vehicle production volume came to around 145,000 units.

With global Electric vehicle (EV) sales less than 2% of overall vehicle sales, Tesla’s competition is not other EVs, its the millions of electric combustion vehicles being produced every year.

What are the key complements for Tesla cars?

Battery tech. And charging infrastructure.

By open sourcing patents, Tesla aimed to foster competition in the EV space, and as a result, in complementary products. As competition increases, prices will fall down, increasing the adoption of EVs and hence benefitting Tesla (and also other EV players).

Example 4: Reliance Jio

Reliance Jio, while originally a telecom player, has morphed into a platform. It aims to derive value from the “value added services” like ecommerce, financial services, content streaming. What is the complement to these value added services? Data.

Jio effectively commoditized data by charging rock bottom prices. By making data ubiquitous, it has shifted value capture from telecom services to these value added services.

(Note: This example probably has more parallels with a loss leader strategy than a commoditizing complements strategy, particularly because unlike the examples above, Jio did not bring down the industry prices by fostering more external competition, it did so by charging lower prices itself).

…

Concluding this with the observations from Gwern’s fantastic article on this topic:

Another way that I like to express that is “create a desert of profitability around you”. By reducing the cost of other links of the value chain, there is more money available to spend on the links you actually generate revenue on. This shifts profits along the value chain to that link…By making the other links free or irrelevant, you reduce the odds that a competitor in those links will strengthen their position..

Thank you for reading! Please share it with people whom you think might find it interesting :)

You can also follow me on Twitter here.