[#14] The accelerating shift from public to private equity

How private equity is gaining (even more) prominence, and the possible implications

Hey! Welcome to Marginal Futility. This blog is my attempt to summarize and share some interesting things I come across, especially related to business, finance and tech. I have previously written about the power law in venture capital, business lessons from Amazon and common errors in estimating market size. You can find the full archive here.

You can subscribe below if you wish to receive updates directly in your mailbox. No spam, ever! :) You can also follow me on Twitter here.

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)

On to today’s article…

Last week has been one of the best weeks for Indian startup ecosystem from a funding perspective.

And the general mood regarding funding from PEs has been this 😅

But if we step back, there has been a massive shift going on worldwide over the past decade - capital being increasingly raised from private markets rather than public markets, declining trend of IPOs, fewer public companies than earlier and companies staying private longer.

This article is an attempt to understand this shift towards private equity as well as look at some possible implications. I have relied mostly on the brilliant paper published by Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan of Morgan Stanley in Aug’20 titled “Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look”. Even though it focusses only on the US market, the broader trends and implications are relevant globally.

I have divided this post into three parts:

How does the shift to private equity look like (that is, in what ways is it manifesting)?

What are the reasons for this shift?

What are the possible implications?

…

How the shift towards private equity is looking like

1️⃣ Increasing investor commitments to PE

First, we look at the investor commitments to buyout and VC funds which has been showing an increasing trend over the years. According to Burgiss data, between 1998 and 2018, the number of active buyout, real estate and credit funds grew from slightly more than 900 to more than 5,500.

One of the most clear indications of the shift towards private equity and other alternative assets has been the changing asset mix of US pension and endowment funds, which collectively manage around USD 600 billion of funds.

2️⃣ Decline in number of listed companies

In USA, companies have raised more money in private markets than in public markets in each year from 2009-2019.

The number of publicly-listed companies in USA has been on the decline since mid-1990s. There are one-half as many public companies as there were in 1996 and three-quarters as many as there were in 1976.

Here’s a look at the trend of IPOs. There were 282 IPOs per year on average from 1976 through 2000 and 115 from 2001 through 2019. While 2020 definitely saw a large number of companies going public (including through SPACs), the overall trend has been pointing downwards

3️⃣ Companies staying private longer

The median age of US companies doing an IPO has been trending upwards. The below exhibit shows that the median age of a company doing an IPO was ~8 years from 1976 to 1997 which increased to ~11 years from 1998 to 2019

Companies that listed in last decade are on average older and larger than those of the prior period.

…

Why is this shift happening?

1️⃣ The quest for ‘alpha’

Perhaps, the most obvious reason is that Institutional investors are looking for excess returns.

For most pension funds and endowments, the primary investors in U.S. private equity, liabilities have increased while expected asset returns have decreased. For example, a large gap has opened between the assets and liabilities for pension funds in the U.S. Estimates for these unfunded pension liabilities run from about USD 1.6 trillion to

USD 6 trillion, depending on the method. There are three levers to reduce the gap: contribute more to the plan, provide less to the beneficiaries, or generate a higher return on the assets under management. Since the first two levers are not popular, most chief investment officers strive for the third.

Buyout funds and VC funds, have on an average, provided better returns that index funds over the last 3 decades.

A BlackRock survey of 230 institutional investors with more than USD 7 trillion under management indicated that 51 per cent intended to cut exposure to public equities. But nearly half planned to put more money into private markets while very few planned to trim. (Source: FT)

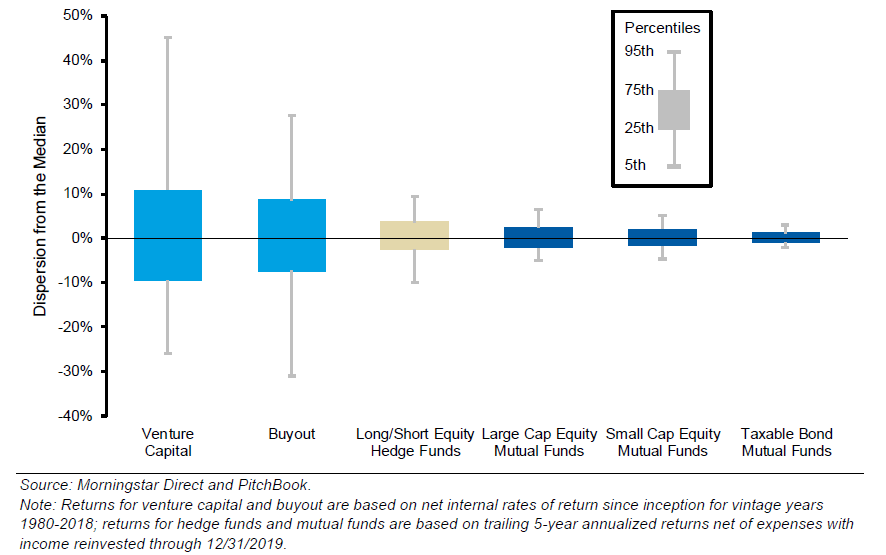

One thing to note here, however, is the high dispersion of returns. Return dispersion, the difference between the best and worst funds, is very wide in private equity relative to other asset classes. Venture capital dispersion is even higher than that of buyouts.

I have written about the power law in VC returns earlier.

2️⃣ The rise of intangible assets leading to lower capital intensity

One hypothesis is that companies simply do not require as much capital as they once did. The below exhibit shows how the mix of tangible and intangible investments has changed over the last 40 years. In the late 1970s tangible investments were nearly double those of intangible investments. Today, intangible investments are one-and-a-half times larger than tangible investment

The shift from tangible to intangible assets has had a meaningful effect on the mix between public and private companies. That many young companies have less capital intensity means they don’t need to go public to raise capital, and can instead rely on private markets

…

What are the possible implications?

1️⃣ Retail (Non-accredited) investors to be allowed to invest in private markets, even if on a limited basis

Access to private markets globally has hitherto been restricted to institutions and individuals who fulfill certain networth and other criteria (known as ‘accredited investors’). For instance, in USA, 98% of the households are not allowed to invest in private funds, as per a 2018 review by Committee on Capital Markets Regulation. 401(K) plans are also not typically allowed to invest in them.

With the growth in popularity of private equity + the increasing number of companies staying private, there has been a long standing demand for relaxing these rules and allowing for retail participation in the private markets.

Over the past couple of years, SEC has released concept notes on allowing retail participation in alternative assets including private equity. The Department of Labour in the USA has also released an information letter on pooled investment vehicles for retail investors, with some allocation to private equity. Vanguard, one of the largest money managers in the world, has struck a partnership with leading PE firm HarbourVest: it is likely that asset allocation vehicles with private equity components will soon become a significant portion of the retail fund market.

While acting as a massive boost to the already high AUM growth rates of PE funds, opening up to retail investors may quite possibly lead to more regulatory oversight, disclosure requirements, changes in fee structures etc.

2️⃣ Alpha to become a bit elusive

Investors may want to allocate more of their portfolios to buyout and venture capital funds, but that desire has to be balanced against the industry’s capacity to absorb funds. Typically, alpha would decline as the AUM grows >> As the AUM grows, the opportunity set would keep shrinking, and more money chasing the same or fewer set of deals would lead to higher valuations, thus lowering the returns possibly.

As we saw above, the number of funds has been increasing rapidly. Moreover, firms are now willing to enter each others’ markets. Buyout funds are now also dabbling in growth and sometimes early stage investing, while VC firms are moving up the chain and getting into growth equity. Hedge funds are also entering private equity space (for instance, Two Sigma, a leading quantitative hedge fund has raised a venture capital fund).

3️⃣ Increasing shift towards emerging economies like India

As more capital flows into the PE, firms will be increasingly challenged to effectively deploy it. The focus is probably going to shift towards regions and segments which are under-developed from a private funding perspective.

According to data from the Emerging Markets Private Equity Association (EMPEA), PE activity in the emerging markets represented 23% of global PE investment activity in 2018, up from just 9% a decade ago.

The penetration of PE (measured as PE investments as % of GDP) is still very low in emerging countries.

These are the economies which are growing at rates much faster than developed economies, and hence, there is a high likelihood of PE funds increasing their commitments towards emerging markets, including India.

…

We have come a full circle, starting out with how there seems to be funding frenzy in Indian startups, and ending with how it is only set to increase. 🚀

Interesting things I read this week

1. The Indus Valley Playbook (Sajith Pai)

On the evolution of the Indian startup ecosystem, or Indus Valley, and the distinct set of hacks and business models that have evolved to help Indian startups win — The Indus Valley playbook

2. Finance as Culture (John Luttig)

Financialization is no longer purely institutional; it has seeped into our culture. A combination of low interest rates, a historic tech bull run, and the resulting torrent of FOMO has tethered us to our monitors to watch candlestick charts. The financialization of culture has manifested in two primary ways: lottery culture and equity culture

Thank you for reading! Please share it with people who you think might find it interesting :)

You can also follow me on Twitter here.

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)

Love the analysis Arpit!

Is there a way for individual investors to invest in buyouts or VC funding?