[#16] On Speed as a moat, Indian consumer pyramid and why Value Investing isn't dead

Hey! Welcome to Marginal Futility. This blog is my attempt to summarize and share some interesting things I come across, especially related to business, finance and tech. I have previously written about the power law in venture capital, business lessons from Amazon and common errors in estimating market size. You can find the full archive here.

You can subscribe below if you wish to receive updates directly in your mailbox. No spam, ever! :) You can also follow me on Twitter here.

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)

On to today’s post…

Speed as a moat

I recently read a couple of amazing articles on Tiger Global, the USD 65 billion cross-over PE / hedge fund.

From the article in Morning Context,

It would seem that in 2021, 72 hours is all it takes Tiger Global Management to decide if it is investing $20 million or less in your startup. Anything longer, and chances are that Tiger isn’t interested…

In the last six months, the firm has already cut cheques amounting to upwards of $1.3 billion. No other venture firm comes close in terms of this level of capital commitment in this short a time.

And from Everett Randle’s must read piece “Playing Different Games”,

In the past two years, Tiger has developed an entirely unique investment platform in venture/growth based on Maximum Deployment Velocity and Better/ Faster/ Cheaper Capital for Founders.

While the jury is still out whether the model of turbo-charged deployment velocity makes sense in the investing world and whether this approach could be doing more harm than good, these articles reminded me of a tweet thread by Hemant Mohapatra, partner at Lightspeed India.

Hemant gives instances of Amazon (Prime), SpaceX (Starlink) and Pfizer (Covid vaccine) to drive the point of how speed can be a huge competitive advantage.

In the context of companies, what are the building blocks of speed?

Making decisions faster + executing decisions faster.

Let’s talk about making decisions faster.

Perhaps the best blueprint for this comes from Jeff Bezos’ letters to shareholders (2015 and 2016):

To keep the energy and dynamism of Day 1, you have to somehow make high-quality, high-velocity decisions.

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions. But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors. If you’ve made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you don’t have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. Plus, either way, you need to be good at quickly recognizing and correcting bad decisions. If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure.

As far as executing faster goes, I found this First Round Review article by Dave Girouard (CEO of Upstart) very helpful. He discusses a number of ways in which ‘speed in execution’ can be turned into a habit at companies. The one which stuck with me - “Challenge the When”

There’s a funny story about my old pal Sabih Khan, who worked in Operations at Apple when I was a product manager there. In 2008, he was meeting with Tim Cook about a production snafu in China. Tim said, “This is bad. Someone ought to get over there.” Thirty minutes went by and the conversation moved to other topics. Suddenly Tim looked back at Sabih and asked, 'Why are you still here?' Sabih left the meeting immediately, drove directly to San Francisco Airport, got on the next flight to China without even a change of clothes. But you can bet that problem was resolved fast.

So, is speed a moat?

The Online Consumption Pyramid in India

The Ken recently carried an interesting article “Why India won’t see a $100 billion internet company anytime soon”.

This is the reason they give:

The number of active internet customers in India has stopped growing. This customer base represents the total addressable market for most Indian internet companies. Until now, this market was growing rapidly.

Now, this growth has essentially flatlined.

Haresh Chawla, partner at True North, had written about this phenomenon earlier. He says that India is not one market, but a combination of three markets.

The failure to distinguish between “internet users” (India Two) and “internet consumers” (India One) has messed up every estimate of the market.

In a real sense, TAM—of people who can afford to actually habitually spend on the current offerings of our internet giants—is not one billion people, it is about 150 million people. A sixth of the total!

E-commerce players talk about how their penetration levels are low and they have a huge upside. But the moment you redefine the addressable base—i.e. assume it’s not 250 million households but closer to 40-50 million with discretionary income—our online shopping penetration suddenly rivals the best markets in the world.

From the Ken article, it appears that even India 1 is not a homogeneous group. At the highest level, we have around 10 million users who transact online actively.

Zomato reported an average monthly transacting user base of 10 million users. Netflix has about 3 million subscribers in India. CRED claims to have about 6 million. Amazon Prime has 6-7 million users.

Monetization becomes a challenge as we go down the pyramid - and hence, the growth in ecommerce in India would be closely tied to the growth (and more importantly equitable growth) in per-capita GDP of India - Till this parameter improves materially (leading to a bigger India 1), consumer Internet cos in India would be competing over the same set of customers, trying to increase the wallet share while moving more spend from offline to online.

Why value investing isn’t dead

Came across a brilliant research paper by Sparkline Capital which shows that the reason ‘traditional’ value investing has struggled in the past few years is due to focus solely on tangible assets.

Some excerpts below, I wrote a more detailed thread on Twitter.

The principles of value investing were established in days of railroads & steel mills. However, economy has transformed from industrial to information-based. Today’s dominant firms build moats using not physical but intangible assets, such as IP, human capital, and network effects.

The most important / valuable industries today are asset-light. As seen below, the % of U.S. public company market cap in high-intangible industries has grown from around 0% to 50% over the past century.

However, the current construct of financial statements and accounting standards, developed decades ago, does not lend itself very well to valuation of intangible assets. Table below shows how GAAP accounting treats each of the four intangible pillars (or doesn’t, as is often the case).

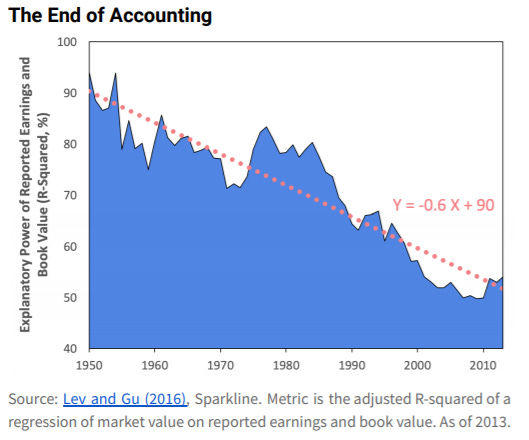

Hence, metrics like book value and reported earnings have been steadily losing explanatory power (at rate of 6% per decade). This is quite concerning as book value and earnings anchor two widely used valuation ratios (i.e., P/E and P/B).

Hence, we need to move beyond the limited information in financial statements. We need to find ways to directly quantify the value of intangible assets, opposed to just the historical costs of their creation. Data for intangible assets, however, is unfortunately unstructured – the paper shows how machine learning and Natural Language Processing can be used to value intangibles.

Using this technique, they demonstrate that value investing has actually worked reasonably well, as long as you avoid running it on high intangible companies.

The bad news is that the universe of companies for which tangible value still matters is steadily and irrevocably shrinking.

Value investing simply means buying stocks below intrinsic value. And intrinsic value absolutely should take into account firms' growth prospects. If large % of growth is coming from intangibles, investors should learn how to value them.

Thank you for reading! Please share it with people who you think might find it interesting :)

You can also follow me on Twitter here.

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)