[#22] On Blume Ventures' Indus Valley report

Narratives and numbers on the Indian economy and startup ecosystem

Hey! Welcome to Marginal Futility. Here, I share interesting things I come across, especially related to business, finance and tech. You can find my previous posts here.

You can subscribe below to join 1,000+ readers who receive updates directly in their mailbox. No spam, ever! :) You can also follow me on Twitter here.

On to today’s post.

Amal Vats and Sajith Pai of Blume Ventures recently released the 2nd edition of their highly popular “Indus Valley Annual Report” about the Indian startup ecosystem.

In their own words - “We didn’t create it to serve as an exhaustive repository of data or reportage on India. Rather, it is more a narrative, and less a dataguide. Or even better, you should see it as a source of perspective on the Indian startup ecosystem.”

While the entire report is ofcourse worthy of being read, re-read and referred to (you can do so here); I found a few perspectives quite interesting which I am sharing below; along with some additional data points.

1️⃣ India is a consumption-driven economy and will remain so

Private consumption is almost 60% of India’s GDP, as against 38% for China.

As per Morgan Stanley estimates; India’s private consumption will more than double from US$2trn in 2022 to US$4.5trn by the end of the decade (accounting for ~58% of forecasted GDP), a size that would be roughly similar to China in 2015. The following chart by Morgan Stanley depicts how several drivers will work together to drive the India consumption engine.

While the Indian consumption is significantly skewed towards food (40% share in consumer expenditure), as the per capita incomes increase, the mix would shift towards higher discretionary spend.

The major boost to consumer activity will likely occur in the discretionary consumption space. Consumer spending is already on the rise, as per-capita GDP has crossed the US$2,000 mark. Discretionary consumption will see a big shift when per-capita income rises above US$2,000, as observed globally. As that level is passed and moves toward US$5,000 by 2031, incremental income will be spent on discretionary goods and services and household expenditure will look very different from the past.

The trend is already visible.

….

2️⃣ However, only a small % of population drives the consumption engine

Haresh Chawla, partner at True North, has also written about this phenomenon.

If you stacked up a 100 Indians, here’s how our income distribution looks:

1 Indian earns 30% of the total and makes over Rs 1.5 lakh a month

14 Indians earn 30% of the total and make around Rs 20,000 a month each

The next 30 Indians earn 30% of the total and make Rs 8,000 per month each

The poorest 55 Indians earn 10% of the total and make only Rs 1,500 per month each

This of course holds true even more for ecommerce and digital economy startups. Blume Ventures has come up with a very good representation of how the Indian consumer pyramid looks like - India is not one market, but three markets. And India 1 is where most of the monetizable users are.

While the headline number of 700mn+ internet subscribers in India is definitely commendable, the user base narrows sharply as we move towards paid services

Monetization becomes a challenge as we go down the pyramid - and hence, the growth in ecommerce in India would be closely tied to the growth (and more importantly equitable growth) in per-capita GDP of India - which will be a slow process.

….

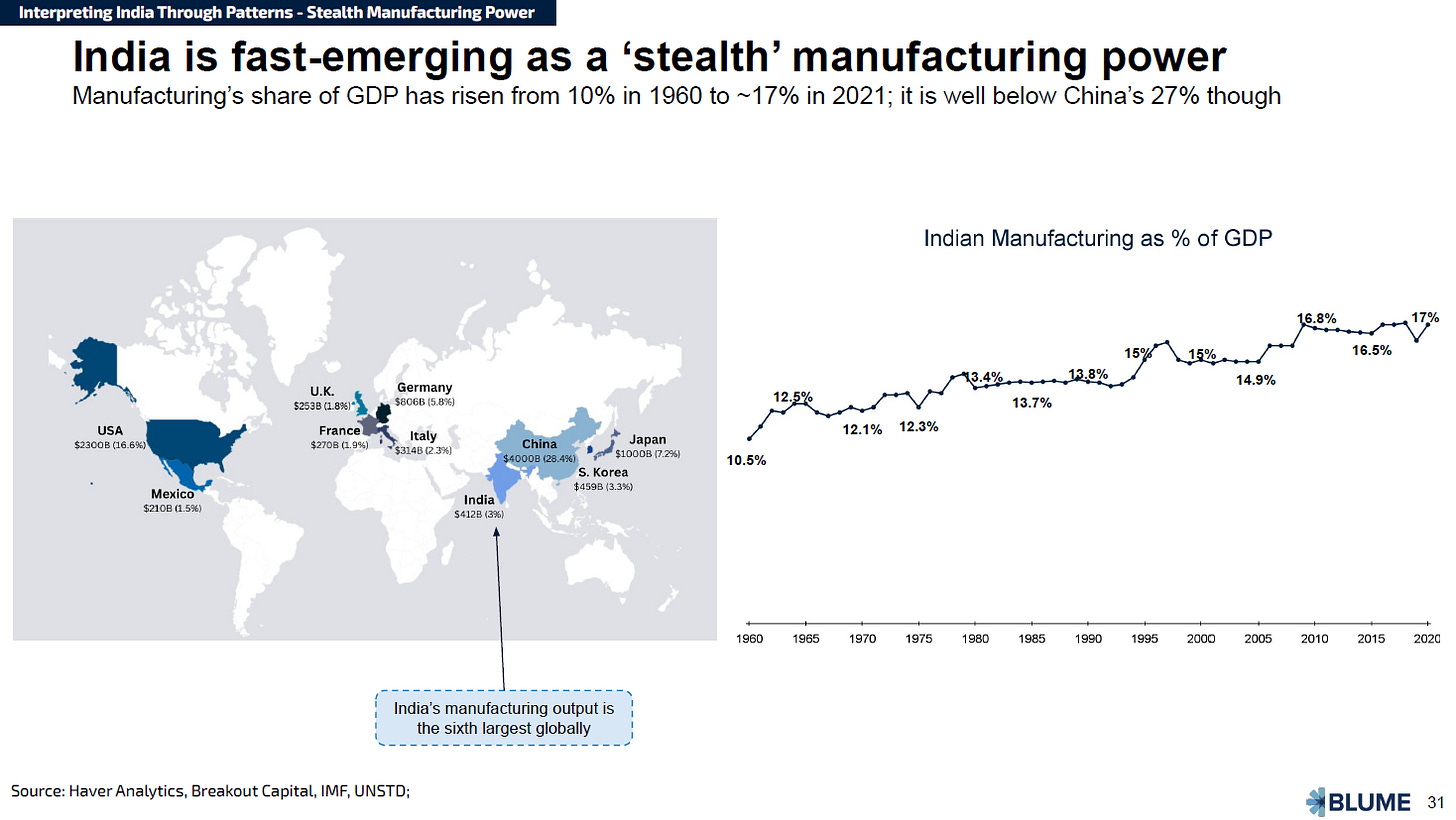

3️⃣ India is slowly emerging as a manufacturing power, but a lot remains to be done

With tailwinds like government incentives like PLI, India’s low labour costs and large labour force and a strong capex cycle and a gradual shift of production away from China, share of manufacturing in India’s GDP has been increasing.

Morgan Stanley estimates that manufacturing as a share of GDP will increase from ~16-17% currently to 21% by 2031.

While there is cause for optimism, there is cause for caution as well - given India has already had a decade of opportunity to scoop up the industrial production leaving China and has ended up performing poorly.

In the decade or so since the global financial crisis, China gave up about $150bn of global market share in labour-intensive goods, of which India attracted no more than 10 per cent

…

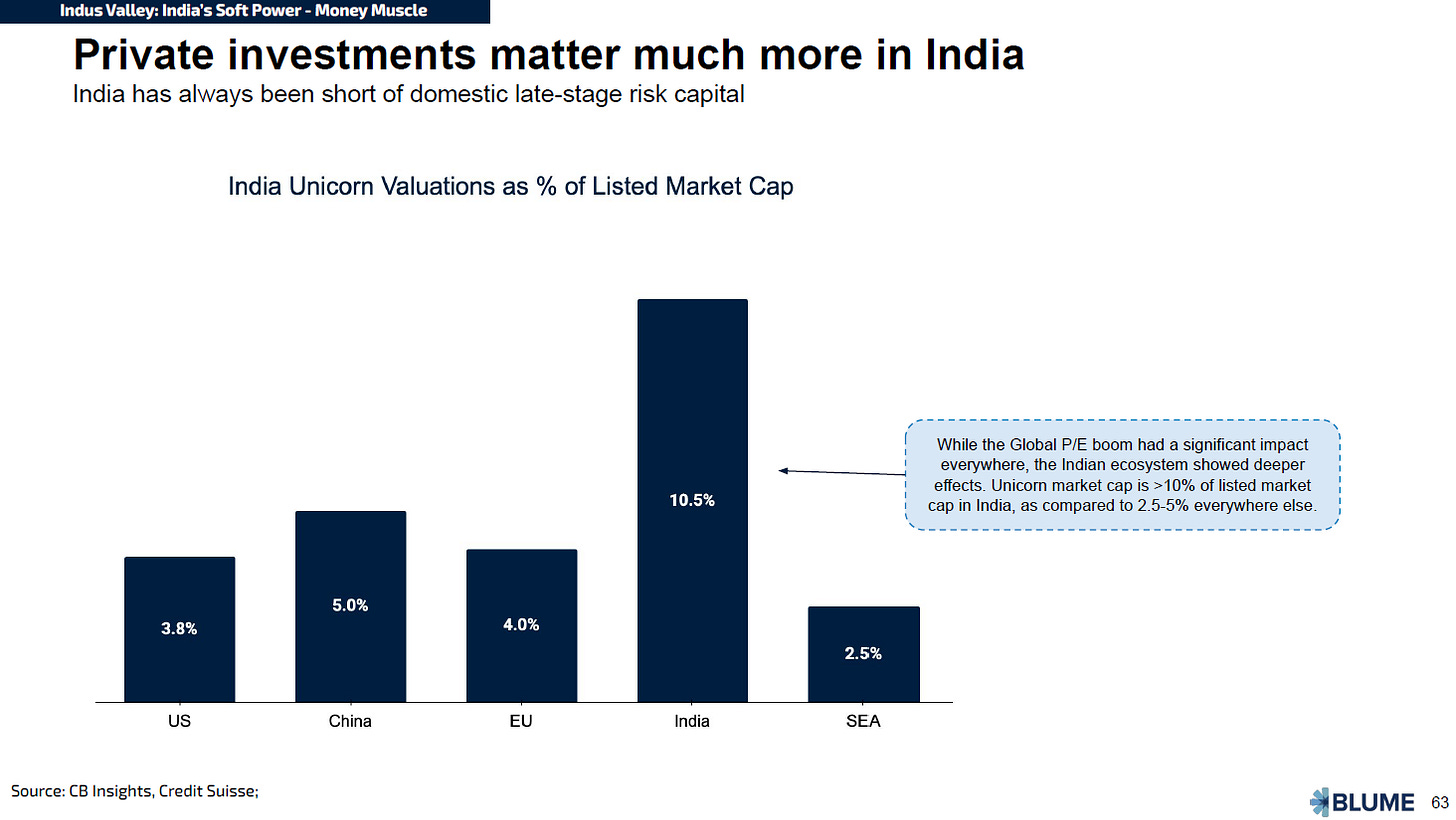

4️⃣ Private money dominates late stage financing in India, which can have some negative consequences

I have earlier written about US companies staying private longer, as a result of higher and higher late stage private financing activity.

The below exhibit shows that the median age of a company doing an IPO was ~8 years from 1976 to 1997 which increased to ~11 years from 1998 to 2019

This trend is even more pronounced in India, with private financing dominating late stage financing.

Without startups listing early, and without an active tech IPO market, India’s tech market capitalisation will continue to see an undersized share (~1.5% of overall market capitalization).

As a result, India unicorn valuations as a % of listed market cap is disproportionately high.

Karthik Reddy of Blume had written this in his IPO trilogy a while back:

The Indian VC-supported startup world doesn’t seem to have come to terms with an important eventuality – Venture cycle completions means companies going public and creating monstrously large public companies that are eventually the source of smaller acquisitions and exits. Without anyone attempting the former, the latter is tougher to achieve

While company building is of course a very long road, it is important to understand how private and public markets reward different things differently. Hypergrowth and profitability are two sides, and companies staying private longer can have unintended effects on their “list-ability” or performance post listing.

Interesting things I read this week

1. The story of how Icahn and GFC, not Netflix, doomed Blockbuster by Arda Capital

This was an eye-opening read. Like many others, I used to believe that Netflix was directly responsible for Blockbuster’s downfall. But that wasn’t really the case. Blockbuster had launched a competing product “Total Access” and was actually winning by a huge margin; until Carl Icahn (the famous investor) launched a proxy fight, got the CEO replaced and shut down Total Access, Blockbuster’s successful but then-money-losing response to Netflix. What a riveting story!

2. Infinite Games by Jack Raines

Here’s the problem with treating life as a series of finite games that must be won: No one remains the winner forever. The finite and infinite player can accomplish the same things, but doing the work for the sake of doing the work will certainly make the journey more enjoyable, won’t it?

Thank you for reading! Please share this post with people who you think would find it interesting :)

You can also follow me on Twitter here.

(Disclaimer: All views expressed in this blog are mine; and do not, in any way, represent the views of my employer.)